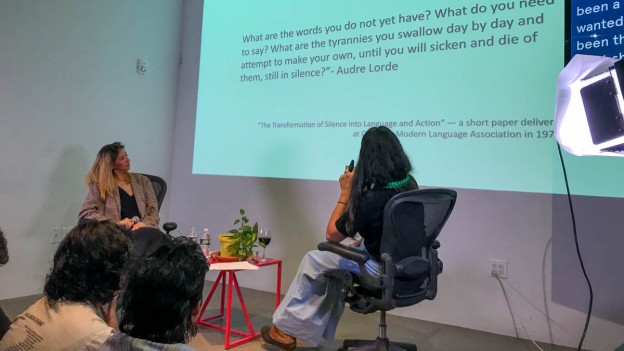

Recently, I attended a presentation by two artists making inquiries into their bodylife stories, Embodied Scores–the poetics of data excavation in the crip body with Yo-Yo Lin and Pelenakeke Brown [1]. You can see the artists above in the photo. That’s Yo-Yo Lin on the left and Pelenakeke (Keke) Brown on the right, reading a quote from Audre Lorde’s essay, “The Transformation of Silence into Language and Action”.

Their methods of inquiry, art-making and storytelling resonated with me. In addition to thinking further about each of them specifically, their bodylives, and for the first time, intentionally considering the individual experiences of disabled or chronically ill or crip bodies (I had not heard the phrase crip bodies before), as well as internalized ableism, it got me thinking about women generally —not to generalize across our experience— but how the need to transform silences, when it comes to female bodylife, is universal.

When it comes to all bodies, there is so much we’re not talking about from an individual bodylife perspective, where we tell our own stories ourselves. It’s too personal to share or to trust our own experiences, the way we do information, data and opinions, provided by doctors, healthcare providers, political, religious and insurance company policymakers, bureaucrats and profiteers in other industries, scientists, researchers or any other “experts”. [1]

Though, personally —uniquely, individually— is how we live so how can our personal experience of our own bodies, not be relevant or valued?

Here’s what Keke read to us: “In the cause of silence, each of us draws the face of her own fear — fear of contempt, of censure, or some judgment, or recognition, of challenge, of annihilation. But most of all, I think, we fear the visibility without which we cannot truly live. …And that visibility which makes us most vulnerable is that which also is the source of our greatest strength.” [2]

Speaking up is not easy. Especially in an environment and culture not designed with us in mind.

What are we gaining in our silence? Or losing in the exclusion and pain of not being seen or heard?

Thank you for witnessing that.

A practice of authentic, witnessed movement

This may have been the most important thing I heard said (and there were many that continue to affect me) — “Thank you for witnessing that.” In this authentic movement practice, Keke is dancing and speaking what she is dancing, with someone witnessing. During her talk, when Keke said the words, “Thank you for witnessing that.” I shook a little inside as if all the memories archived in me, at a cellular level, were considering the possibility of being seen and what it might mean.

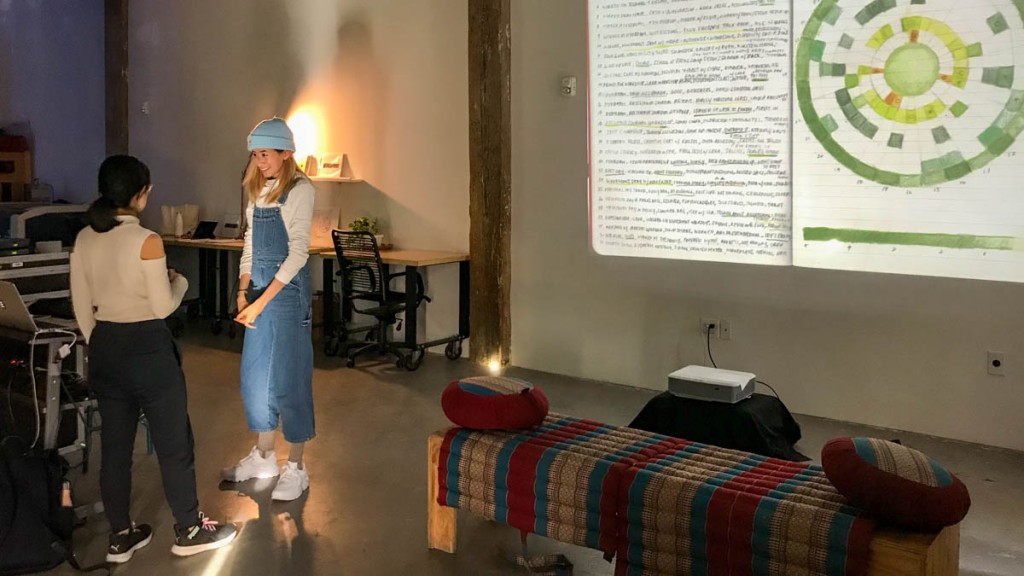

Medical records transformed into poetry

In Excavātion: an archival process, Keke’s practice consisted of requesting and reading through the archive of her medical history (not such a simple things to do) and turning printed pages of it into poetry (as well as movement as in the image above). In the documents of her early history, especially around “her mother’s experience navigating the medical industry”, she was able to see how qualities of her healthcare experience shifted based on the postal code and skin tone of her caregiver, expressing inherent medical racism, and the politicalness of being a brown body in the world.

Blackout poetry is a form that embodies movement and words. What you see on the screens in the images below are projections of Keke’s medical records, much of them blacked out, and the visible words revealing and revaluing lived, and living, experience. Keke used the blackout practice to question who got to have a voice in her medical record…Who is speaking? Who is not speaking?

Keke said we can read it however we want. The captions are my readings. I didn’t transcribe Keke’s when we read them to us. I don’t know whether mine are different.

Collecting soft data

“Soft data is data as human experience — full of opinions, suggestions, interpretations, contradictions and uncertainties”…[3]

Yo-Yo’s Resilience Journal is a physical ritual that she began in January. Her framework of soft data begins with a circle. Each circle is a month; each slice of the circle is a day and has seven dimensions to it, expressed in layers that Yo-Yo colored in with varying intensity to match her day. She also made daily notes on the facing page and incorporated symbols to commemorate certain kinds of moments. In her resilience journal, Yo-Yo is creating an archive of how her illness presents itself, including its overlooked, and sometimes contradictory, aspects.

Instead of coming from a place of needing to be fixed, she tracks what living is like. The seven dimensions of her days that Yo-Yo tracked are:

- Felt it

- Logistical (issues led to asking for help)

- Body image

- Social pressure

- Getting care

- Future visions (enacting in the present)

- Past (trauma, memories brought up)

The symbols are a little hard to see in the image, but if you look carefully, you’ll make out circles, indicating “I accommodated myself” and stars, indicating “People Accommodated”. The other three kinds of repeatable moments being tracked are open triangles, indicating “Someone asked about it”, an “X” indicating “Thought about death” and a filled-in triangle, indicating “Had to explain to someone”.

The monthly visualizations extend attention beyond a catalog of illness, they express healing as a process of continual becoming.

Yo-Yo shares her journal with us from the place of “This illness is not just my own.” The books are available to us, too, to track our own soft data. You can carry a journal with you, wherever you carry your body. I bought a journal and look forward to investigating and tracking…

There was so much that came up for me, as I sat, listening to Yo-Yo and Keke take us through their practices of process-driven art-making out of their personal histories, enlisting multiple media to give expression, visibly, audibly, and through movement, to investigate, record and reshape meaning. I left inspired, intending especially to keep at the project of speaking. I wish you could have been there.

“We can learn to work and speak when we are afraid in the same way we have learned to work and speak when we are tired. For we have been socialized to respect fear more than our own needs for language and definition, and while we wait in silence for that final luxury of fearlessness, the weight of that silence will choke us….it is not difference that immobilizes us, but silence. And there are so many silences to be broken.” [2]

Yo-Yo had posted on Instagram that she would be there on Sunday, so I came back to Eyebeam to take time viewing the work. Also, I hoped to talk with her. I did get that chance. Here she is with her friend (whose name I wish I had noted down!) her cap glowing.

References

[1] Embodied Scores–the poetics of data excavation in the crip body with Yo-Yo Lin and Pelenakeke Brown, taking place at Eyebeam in Bushwick on 12/04/2019, presented by Eyebeam Assembly in partnership with Denniston Hill and The Laundromat Project. For more on the event…

[2] “The Transformation of Silence into Language and Action”. Paper delivered at the Modern Language Association’s “Lesbian and Literature Panel,” Chicago, Illinois, December 28, 1977. First published in Sinister Wisdom 6 (1978) and The Cancer Journals (Spinsters, Ink, San Francisco, 1980).

[3] Yo-Yo Lin: Resilience Journal, 2019.

[4] Penelakeke Brown: Excavātion: an archival process, 2019.